When Annie Burke died in 1962, she left her daughter with an important but daunting request.

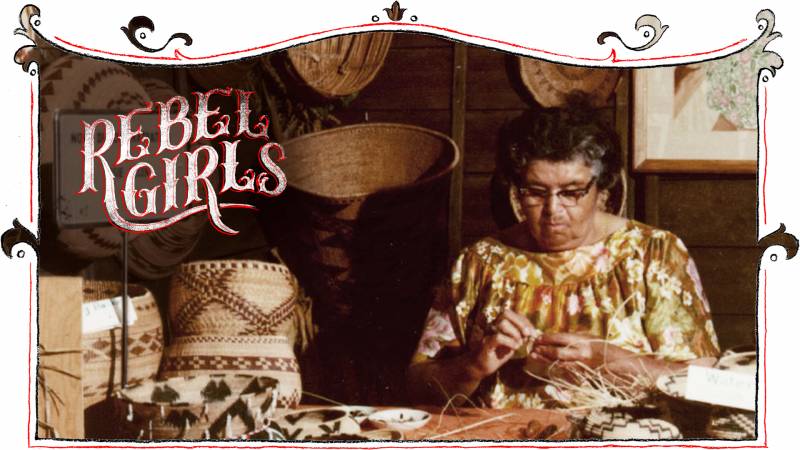

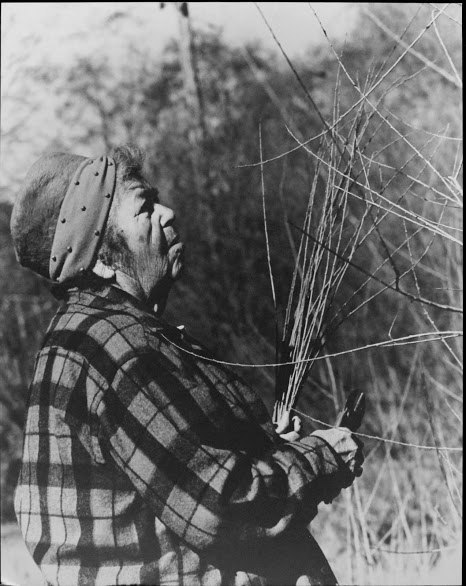

Annie and her daughter Elsie Allen were Pomo—a Native people whose traditions dictated that women’s intricately hand-crafted baskets were always buried with them or other relatives. Burke asked her daughter to instead keep her baskets, pass them down, and use them to educate future generations of both Pomo people and the outsiders who looked down on them.

Not only did Elsie Allen fulfill her mother’s dying wish, she also built a platform to fight for Native American civil rights, equal education opportunities, and greater visibility in the world.

Elsie Allen was born on Sept. 22, 1899 in Cloverdale, north of Santa Rosa, to farm laborers George and Annie Comanche. Though the first few years of her life were fairly idyllic, Allen encountered hardship early. Her father died when she was eight. By the time she turned 10, she was working in the fields alongside her mother. At the age of 11, she was forced by the government to attend an English-speaking boarding school 80 miles north of her Hopland home, despite having only ever spoken Pomo. She, like many Native children forced into the “Indian Boarding Schools” of the time, struggled there and later counted it as one of the worst times of her life.

Once a new school opened in Hopland, Allen was able to return home, learn English and receive a formal education. But she never stopped working, throughout her teens as a farm laborer and, once she was 18, as a domestic servant in San Francisco. She enjoyed neither the tight household restrictions nor the discrimination to which she was subjected, and within a year, went to work as a custodian at St. Joseph’s Hospital in San Francisco instead.